Britain’s islands are home to a remarkable array of wildlife, some of which is endemic. Given how small our country is, isn’t it astonishing that we are home to organisms that can be found nowhere else on Earth? These unique creatures, shaped by isolation and distinct environmental conditions, offer a fascinating glimpse into the power of evolution. From tiny insects to charismatic mammals, Britain’s endemic species tell a story of adaptation and survival. Many of these animals face challenges due to habitat loss and climate change, making their conservation so important.

Scottish Wildcat

Often called the “Tiger of the Highlands,” the Scottish wildcat is Britain’s only remaining native feline. These fierce predators are slightly larger than domestic cats and have distinctive striped fur. Sadly, they’re critically endangered due to habitat loss and interbreeding with domestic cats. Conservation efforts are underway to protect these elusive and beautiful animals. Scottish wildcats can survive in temperatures as low as -20°C thanks to their thick, water-resistant coat, making them well-adapted to the harsh Highland winters.

New Forest Cicada

This small insect is the only cicada native to Britain. It’s known for its loud, high-pitched song, which can be heard on warm summer days in the New Forest. Despite extensive searches, the New Forest cicada hasn’t been seen since 2000. Scientists now use smartphone apps to try and detect its call, hoping to prove it still survives. The cicada’s lifecycle is unique, with nymphs living underground for up to 8 years before emerging as adults for just a few weeks.

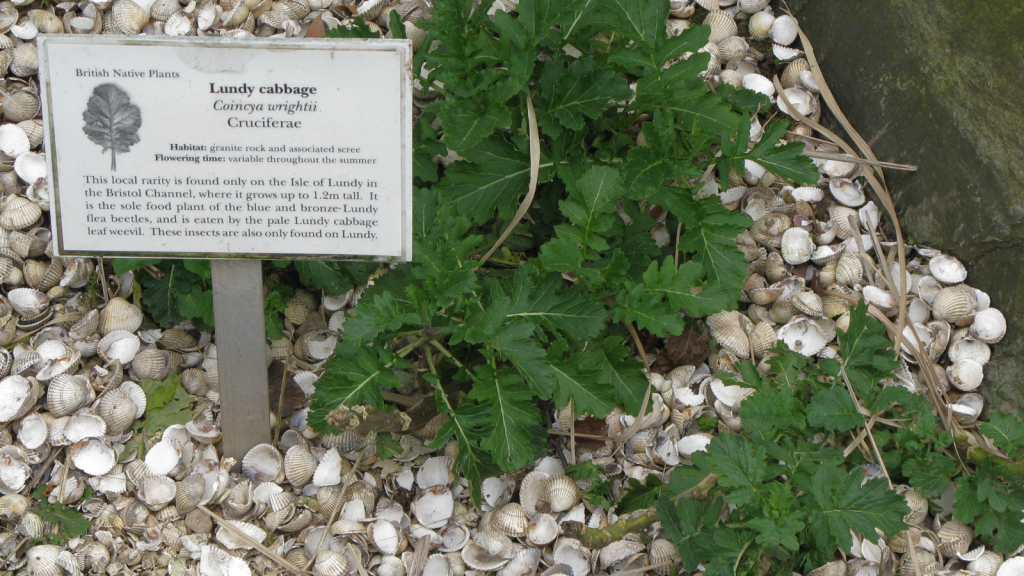

Lundy Cabbage

While not an animal, this plant hosts two unique insects. The Lundy cabbage flea beetle and the Lundy cabbage weevil are found nowhere else in the world. Both insects depend entirely on this rare plant, which grows only on the island of Lundy off the coast of Devon. The survival of these tiny beetles is tied directly to the conservation of their host plant. Lundy cabbage has evolved to thrive in the harsh, wind-swept conditions of the island, with thick, waxy leaves that help it retain water.

Red Grouse

This game bird is found in the heather moorlands of Britain and Ireland. It’s the only bird species endemic to the British Isles. Red grouse are famous for their explosive take-off and fast, low flight. They’re also known for changing their diet seasonally, eating heather shoots in summer and buds in winter. Red grouse have specialized gut bacteria that help them digest tough heather, an adaptation unique among birds.

Orkney Vole

This small rodent is found only on the Orkney Islands off the north coast of Scotland. It’s larger and darker than its mainland relatives. Orkney voles are thought to have been introduced by Neolithic farmers about 5,000 years ago. They’ve since evolved into a distinct species, showcasing how isolation can drive evolution. Orkney voles play a crucial role in the islands’ ecosystem, serving as a primary food source for birds of prey like the short-eared owl.

Scilly Shrew

This tiny mammal is found only on the Isles of Scilly off the coast of Cornwall. It’s smaller than mainland shrews and has different teeth. The Scilly shrew likely arrived on the islands during the last ice age when sea levels were lower. It’s a prime example of island dwarfism, where animals evolve to be smaller due to limited resources. Despite their small size, Scilly shrews have a voracious appetite and must eat almost constantly to maintain their high metabolism.

Pool Frog

Once thought extinct in Britain, this amphibian was rediscovered and reintroduced to its native habitat in Norfolk. It’s Britain’s rarest amphibian and the only frog species native to the country. Pool frogs are known for their loud calls during breeding season and their preference for warm, shallow ponds. Unlike other British frogs, pool frogs can produce a weak toxin in their skin as a defense against predators.

Cornish Path Moss

This rare moss is found only in Cornwall, growing on earth banks along lanes and footpaths. It was discovered in 1963 and has fascinated botanists ever since. The Cornish path moss showcases how even the smallest organisms can be unique to a specific area. This moss has adapted to thrive in the mildly acidic, nutrient-poor soils typical of Cornish hedgebanks, demonstrating remarkable specialization.

Llangollen Whitebeam

This tree is found only in the Eglwyseg Valley in Wales. It’s thought to be a hybrid between two other whitebeam species. The Llangollen whitebeam is critically endangered, with only 17 trees known to exist in the wild. Its rarity highlights the importance of protecting even small populations of unique species. The tree’s ability to cling to steep limestone cliffs showcases its remarkable adaptation to its specific habitat.

Scottish Crossbill

This bird is Britain’s only endemic bird species that’s found nowhere else in the world. It lives in the Caledonian forests of Scotland. Scottish crossbills have a unique beak shape that’s perfectly adapted for extracting seeds from pine cones. They’re a prime example of how animals can evolve to fit specific ecological niches. Interestingly, male and female Scottish crossbills can have differently shaped beaks, allowing them to exploit different food sources and reduce competition within the species.

Radnor Lily

This delicate flower is found only in a small area of Radnorshire in Wales. It’s one of Britain’s rarest plants, with only a few hundred individuals left in the wild. The Radnor lily blooms for just a few weeks each year, making it a special sight for those lucky enough to spot it. The lily has adapted to grow on steep, north-facing slopes, which protects it from direct sunlight and helps maintain the cool, moist conditions it prefers.

St Kilda Wren

This small bird is a subspecies of wren found only on the remote St Kilda archipelago off the west coast of Scotland. It’s larger and darker than mainland wrens. The St Kilda wren has adapted to the harsh, treeless environment of the islands, nesting in stone walls and cliffs. Its stronger legs and feet, compared to mainland wrens, allow it to clamber over rocks and cliffs with ease, a crucial adaptation for its unique habitat.

Lindisfarne Helleborine

This orchid is found only on Holy Island off the coast of Northumberland. It grows in the dune slacks of the island, blooming in late summer. The Lindisfarne helleborine is thought to be a hybrid between two other orchid species. Its unique habitat requirements make it particularly vulnerable to environmental changes. The orchid has developed a symbiotic relationship with specific fungi in the dune soil, which help it absorb nutrients in its nutrient-poor habitat.

Northern Ranges Diving Beetle

This small aquatic beetle is found only in a handful of ponds in the Yorkshire Dales National Park. It was discovered in 2004 and is one of the rarest water beetles in Britain. The Northern Ranges diving beetle is adapted to live in cold, nutrient-poor upland ponds. Its limited range makes it particularly vulnerable to habitat changes and pollution. Scientists believe this species may have survived the last ice age in small ice-free refuges, evolving in isolation to become a unique species found nowhere else in the world.

Natterjack Toad

While not strictly endemic to Britain, the natterjack toad is found only in Britain and a few other European countries. In Britain, it’s confined to coastal areas. Natterjack toads are known for their distinctive yellow stripe down their back and their loud mating call. They’re the UK’s loudest amphibian, with calls that can be heard up to a mile away. Unlike other British toads, natterjacks are excellent runners, capable of covering ground quickly on their long legs, an adaptation that helps them survive in their open, coastal habitats.